“How could anyone have survived this?” – is what I kept thinking during my tour of Auschwitz last week. I had been thinking it for weeks while I was planning my trip, and I had been thinking it especially the night before my visit, as my friends and I trudged through the streets of Krakow, noses running, faces so frozen it was difficult to make a “P” sound. “How could anyone have survived this?” – was what we kept asking each other in between complaining about wet jeans and shoes, and wind that made our eyes water. Then, the guilt washes over you for every time you’ve ever complained about being cold.I planned a weekend trip to Krakow of all places because I wanted to see Auschwitz. But I was also happy to see the city of Krakow and eat some Polish food, and I will write about that in a separate blog. I wanted to make sure I saw Auschwitz while I had the opportunity, because I have no way of knowing how long I will be in Europe.

Sixty-nine years to the week after the Russian army liberated Auschwitz, my two friends and I (I had been happy to go by myself but was delighted that two American friends wanted to join me) showed up as tourists. It’s a strange thing to visit a place like Auschwitz as a tourist. A place you’ve studied and studied and seen in movies, and then you go there and in addition to absorbing everything and taking lots photographs, you have to think about logistics like getting there, getting a tour, getting back, and packing a snack. Although it seems almost trivial to discuss these logistics when there is so much else to talk about, if you are a tourist in Auschwitz they are crucial.

Getting there from Krakow:

You have several options.

1) You can take an all-inclusive tour, which picks you up from Krakow (maybe even your hotel) and returns you there. It will include a guide at the camp. This is, by far, the most expensive option but probably the most convenient.

2) You can take a train, and then a local bus to the camp. The train is very cheap, but also takes the longest, especially because you have to tack on the local bus ride for the last mile or so. Once you get to the Camp, you buy a ticket and join up with a group tour there.

3) You can take a public bus, which leaves from the central station in the center of town (about a 15 minute walk from your hotel if you’re staying in Old Town). It is also very cheap and faster than the train. They leave every hour or so. Unlike the train, the bus takes you right to the Camp. Same deal, buying a ticket when you get there and joining up with a group.

If you take options 2) or 3), keep in mind you’ll want to time your arrival so that you get there in time to take a tour in your language. If you’re reading this blog, I assume your language is English. But there are also Italian tours.

We took the public bus. Our big concern was getting to the station after breakfast in time to make the 8:30 departure. We made it on time, but it was full and we had to wait anyway. So, folks, plan on getting to the bus super early. We waited around in the bus station until it was time to get on the next one, at 9:30. We arrived at about 11:00 and bought our tickets for the 11:30 English tour. Do be careful when timing your outbound transportation with the start times of the tours in your language.

Another tip, already mentioned. Bring a snack. Even writing that makes me feel kind of spoiled. To be taking a snack to Auschwitz seems almost disrespectful. But, we had been told to do this by people on the internet and by the lady at our hotel, and we were glad we did. It’s a very long tour – about four hours at the Camp plus three hours of bus rides, and there are some vending machines at the visitor’s center, but no real place for lunch. I had a bagel and a banana in my bag and I wolfed them down around 2:00 p.m.

Our tour was given by a Polish man with flawless, almost unaccented English, named Michel. His tour was also flawless. He explained history, recounted anecdotes, and answered questions for hours, all without any dramatization in his delivery because it was unnecessary.

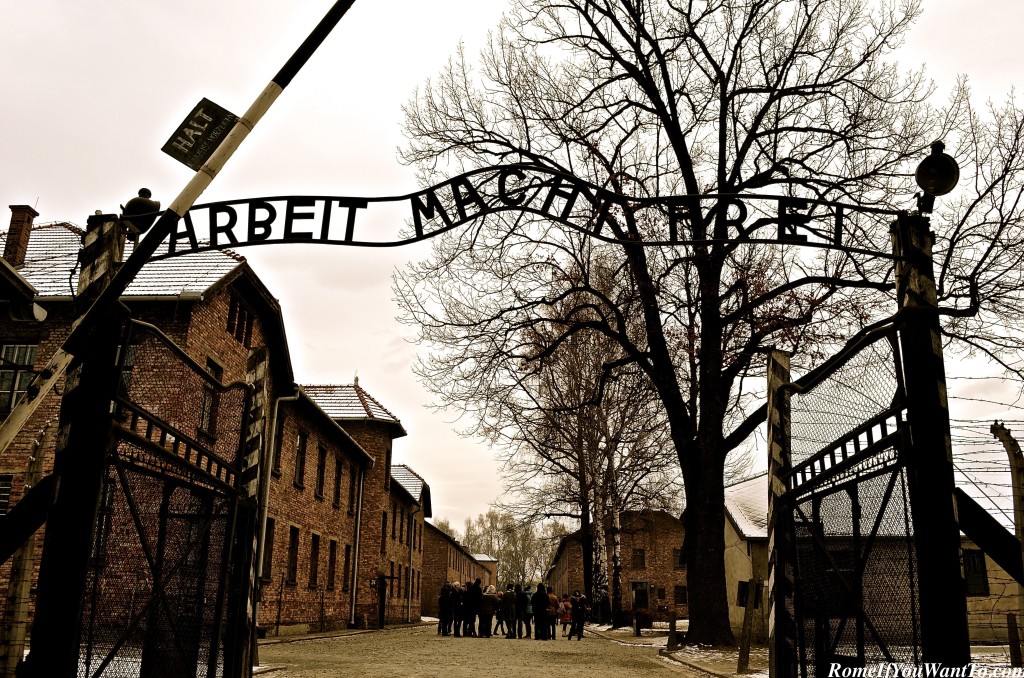

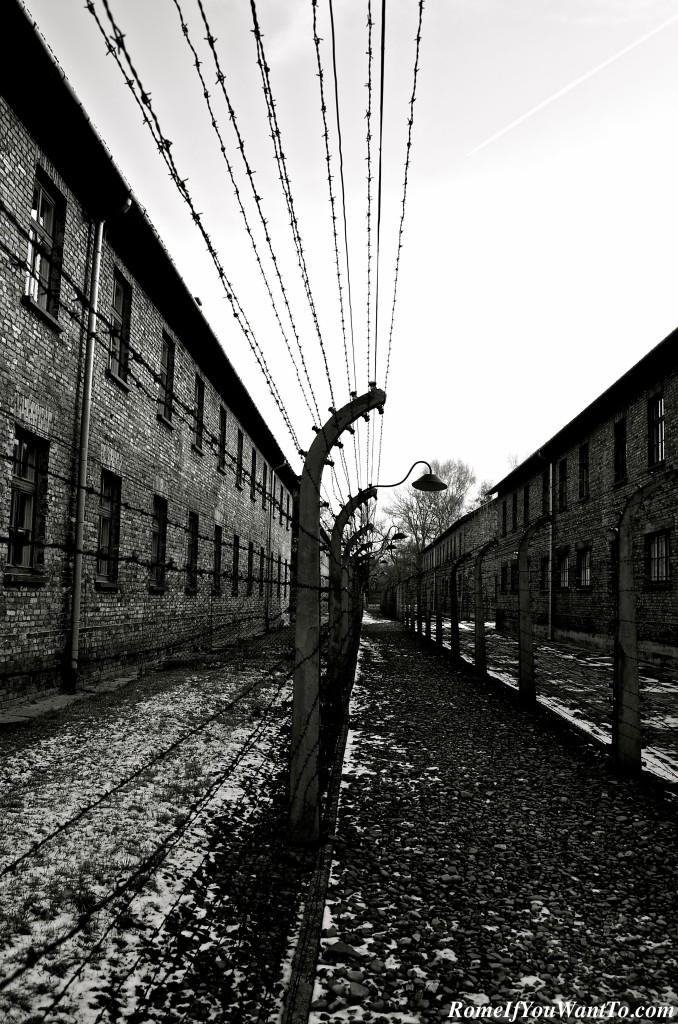

The tour: You leave the ticket pavilion and emerge into a camp crowded with brick barracks. Some are being used as offices for those running the Camp as a historical site. Others contain displays for tourists like us. Others are empty. All are stark. There are many trees, barren in early February, and Michel told us that they were all planted by prisoners during World War II. To the right you see the well-known sign reading Arbeit Macht Frei – Work Will Set You Free. You cross underneath it, just as prisoners once did.

Here, Michel told us something I didn’t know. Many prisoners were let out during the day to work off-site in farms and factories. There was a headcount each evening to ensure they returned. If they did not return, others would be killed as punishment. If a prisoner died while off-site, his body had to be be brought back so that he would be accounted for, and to ensure that he had not escaped.

This part of the tour included walks through former barracks. We saw very well-done displays including two tons of hair that had been shaved from prisoners to make textiles, including a rug, which was also on display. DNA testing on the rug confirmed that it was made from human hair. From looking at it, one would never know.

There were also entire rooms full of shoes, brushes, empty suitcases, crutches and prosthetic limbs (physically handicapped people were immediately killed, but these items were preserved), and eye glasses. I really cannot express how well this site has been turned into a museum. Instead of lining up shoes or putting them in any kind of order, they are thrown in a pile, which was effective. It made me think of bodies in piles. And there are large photographs of those, too.

We also saw ovens for human beings, and large rooms with sprinkler heads for Zyklon B gas, with scratch marks on the walls.

And there are hallways with mugshots of people who were imprisoned there. The people who were killed immediately – too young or too old, or mothers of those who were too young, or the handicapped, or the pregnant – were not photographed. The mugshots included the recorded dates of arrival and death (always death, no survivors on these walls), and usually it was a few months. The reason that healthy mothers were immediately killed, Michel explained, was because when arrivals would pour out of cattle cars and families separated, it was in the guards’ interest that there be no panic. Children were not separated from their mothers, so that they would not scream. This maintained a relative calm, and then mothers and children were exterminated together.

It was after seeing those mugshots and after Michel pointed out the short time span between arrival and death, that I asked myself for the hundredth time, “How did anyone survive this?” Michel read my mind, it seems, and said, “You may be wondering how anyone survived this. A few jobs were considered lucky and greatly increased a prisoner’s chance of survival. Working in the kitchen, for example, where you would be warm and had access to food. Or working in the arrivals area where suitcases were collected and belongings sorted. These prisoners were allowed to eat the food they found, and they found a lot.” Then Michel read my mind again and said, “They were not allowed to eat the food out of kindness, it was so that they would not bring food back to the barracks.”

To keep everybody in line, prisoners were threatened with punishments even worse than the conditions in which they were already living. Isolation cells in which they were kept in the dark, with no food at all (instead of the usual broth and bread), or – horrifying – cells where there was only room to stand. Obviously, for this type of punishment to work as a deterrent, it had to be worse than death.

Michel told us that over 100 people managed to escape Auschwitz. HOW?! I would love to know each of their stories. Michel told us one of them. There was a prisoner who spoke fluent German. He managed to plan with another prisoner to get access to a closet with SS uniforms. Another prisoner was involved who managed to get keys to an SS car. All of these things happened at the same time, and these three, plus a fourth, simply changed clothes and drove out of the camp. Michel told us that the German speaker is still alive, is 95 years old, and visited the camp just two months ago. This was the only time during the very long tour that my eyes welled with tears. There are real heroes walking around this earth and we’re all worried about things like the Superbowl (including me).

This part of the camp is called Auschwitz I. Auschwitz II-Birkenau is a few miles away and your ticket includes transportation to that camp. Large, stretching as far as the eye can see, with barracks that are falling down. This is where you’ll see the latrine room that you know from Schindler’s List (Michel read my mind again when he said, “You may be wondering why there are soap dishes. No, the prisoners were not given soap.”) and the actual three-tiered wooden bunks where prisoners slept. The reason that prisoners tried desperately to get top bunks instead of lower bunks, even killing each other over them (according to Michel), is too gruesome to write.

In Birkenau, you see the long train tracks stretching from the Camp’s gate towards the woods on the opposite end of the camp, and a cattle car that appears able to hold twelve. It held eighty. How did anyone survive this?

What remains of the crematorium. It was destroyed by the SS as the Russians were arriving, and remains today as it was found in 1945.

The tour ended with Michel asking us to tell people what we saw, not only to preserve history for future generations but also to combat the unimaginable belief held by some people that the Holocaust did not happen at all, or has been greatly exaggerated.

A word about this. I personally know two people, one American, one Italian, and both with graduate degrees and professional jobs requiring coats and ties, who do not believe that the Holocaust happened. Obviously, as a person with a brain that actually fills my entire skull and as someone with decades of experience living in reality, I cross-examined both of them on why that is their belief.

Both of them gave me virtually the same answers: We are the sheep, not them. We are brainwashed by Hollywood. The story of the Holocaust is propaganda to further a Jewish, or leftist, agenda. The Camps? They’re fake. Those photos? Well, we saw hundreds, not millions or even thousands. See? The people who once existed and then ceased to exist? No proof can satisfy these two, and those like them, that those victims ever existed in the first place. The Diary of Anne Frank? Fiction. There were answers for every single one of my challenges, and each one more disturbing than the last. Is it just too horrible for them to believe? The horribleness is the same for everyone, so why some people seem to be so willfully delusional, so intentionally ignorant, is a question for a psychiatrist.

Friends, I cannot recommend more strongly a visit to this place. A lifetime of education squeezed into a day, leaving all three of us with more questions than we started with.

********

If you like silliness and distractions from work, or miss my Random English posts, consider liking my Facebook page for daily funnies! And why not get this blog in your email? Use the handy link below.

Thank you for the poignant and beautiful article on such a horrible time in our world’s history. I cannot fathom that there are people who still deny this atrocity!! My husband went to college with an older women who was a survivor; she even had the tattoo on her arm. Unfortunately there was a neanderthal in the class who thought she was a liar and it was all a “plot”. (They probably don’t believe we landed on the moon either!)I shed tears as I stared at Anne Frank’s diary in Amsterdam; unable to make sense of why this happened, other than men can just be evil. I have read “Night” and came away truly admiring Elie Weisel and others who lived through that aweful time. Another book that is great is “A Lucky Child” by Thomas Buergenthal. It’s just a little bit longer than “Night” but just as gripping.

Keep up the posts, I always get a kick out of them! I hope your dreams of writing come true for you very soon! I particularly like the way you plot out how to travel to places, different options for the traveler, plus you are funny! You are the female version of Rick Steves, minus his nerdiness! I love Rick!

Take Care, Sharon

Hi Sharon, thanks for reading and commenting! It is unimaginable, isn’t it, that people (educated people!) choose to believe this didn’t happen. If one can do that, why not believe the Civil War didn’t happen? Or anything else. It is baffling. Thank you for the book recommendations. I’ve got a list I want to see now and these are on it. And thank you for the kind words about my blog. I love Rick Steves! If I could turn this blog into more paying gigs I’d be the happiest girl around, and that’s the truth! Please keep in touch. Hugs, Liz

Pingback: Easy, Freezy, Weekend in Krakow | Rome...If You Want To.Rome…If You Want To.

Grazie per questo bellissimo reportage che hai fatto !

Per tutti quelli che non sono ritornati!

Anna

Sei gentilissima!! Grazie a te! E sono d’accordo, per tutti quelli che non dobbiamo mai dimenticare.