My visit home to Nashville last month wasn’t the usual 24/7 pajama party that it usually is. In addition to Grandma, we had my aunt and uncle and two cousins visiting from Boston, Santa Barbara, and West Point, respectively. This meant that instead of spending our days with I Love Lucy re-runs and football, we actually did a little sight-seeing in the city that the New York Times just listed as #15 on its list of 50 places to see in 2014.

One cold but sunny morning just after Christmas, five of us, all giants compared to the average human, piled into my father’s SUV, and headed away from town towards the Natchez Trace.

I grew up my whole life hearing about the Natchez Trace, but hadn’t seen it. I was aware only that it was an ancient road (I was thinking, “like the Appian Way in Rome!” – yeah, just like that), running from Nashville to Natchez, Mississippi. Given that the road is 440 years old, while Nashville and Natchez are only about 250 years old, for centuries the road apparently led Native Americans from one bit of undeveloped forrest to another.

The original Natchez trace can be hiked, but not driven on. For that, the National Park Service has built an asphalt roadway that runs along side the original path, and is flanked by either side by glorious green farmland. The National Park Service owns the trace and the paved road alongside it, but the land around it is private. Fortunately, the landowners do not build condos; they build barns and farms and the result is pure charm.

“A Very Old Trail.”

All along the Natchez Trace. My aunt, from Boston, kept remarking how beautiful these fences are.

The Old Trace, there for hundreds of years, running alongside the modern roadway.

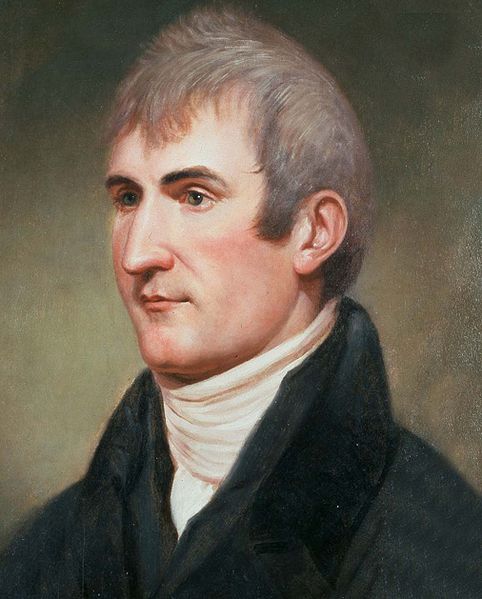

About an hour from Nashville, driving along the Trace, is the site of one of the saddest moments in American history. Meriweather Lewis, at age 27, left the known world on the East coast of North America, for the completely unknown West, where reports and theories had indicated that he and his partner William Clark would find woolly mammoths, mastodons, and bears the size of houses. He knew that if he ever saw his loved ones again – and that was a big “if” – it would be years later. The exploration of the West was crucial; President Jefferson had just purchased most of what we now call “America” from the French, but no one knew how big it was or what was out there. “No one,” of course, except for the millions of human beings who had successfully occupied that land for thousands of years.

The diaries Lewis kept during the three-year journey that followed are meticulous and invaluable to historians, naturalists, and even medical professionals, as Lewis described his treating of the other explorers’ ailments with mercury, among other things. The diaries are also riveting, suspenseful, and seep intelligence. They are furthermore remarkable for the unexplained lapses in time, during which Lewis went from lengthy, detailed entries to silence, for months. What this indicates to historians is that, possibly, Meriweather Lewis was suffering from the illness that apparently ran rampant in his family – severe depression, even bipolar disorder. Assuming this is true, the willpower Lewis must have had in order to keep one foot in front of the other throughout this harrowing, three-year ordeal is extraordinary.

Back in Louisiana three years later, with the hero’s parades and welcome-home kisses fading into memory, and drowning in debt and alcohol, Lewis was summoned to Washington to settle up some loans with the War Department. Accompanied by his African-American slaves, he departed on horseback northbound on the Old Natchez Trace. What was going through his mind during those lonely moments in the woods can only be imagined. After days of riding, just south of Nashville, he and his slaves stopped for the night at Grinder’s Stand, a small boarding house run by Mrs. Grinder, whose husband was away.

What happened next is subject to some debate. The most accepted story is an amalgamation of the various versions told by the only other person in the house that night, Mrs. Grinder. Mrs. Grinder and Lewis had dinner together. Lewis frequently muttered to himself and gesticulated as if he were in court. His face would flush and he seemed to be emotional. They retired to their separate rooms. Mrs. Grinder continued to hear him talking to himself and pacing. Then she heard a gunshot, and then more gunshots. Terrified, she waited until morning to summon Lewis’s slaves, who found him on his bed, full of self-inflicted wounds, including one to the head. There is a report that part of his skull was missing and another report that he continued to breathe for a few hours despite his unspeakably severe injuries.

He was 35 years old. Just a year older than I.

Meriweather Lewis, 1774-1809.

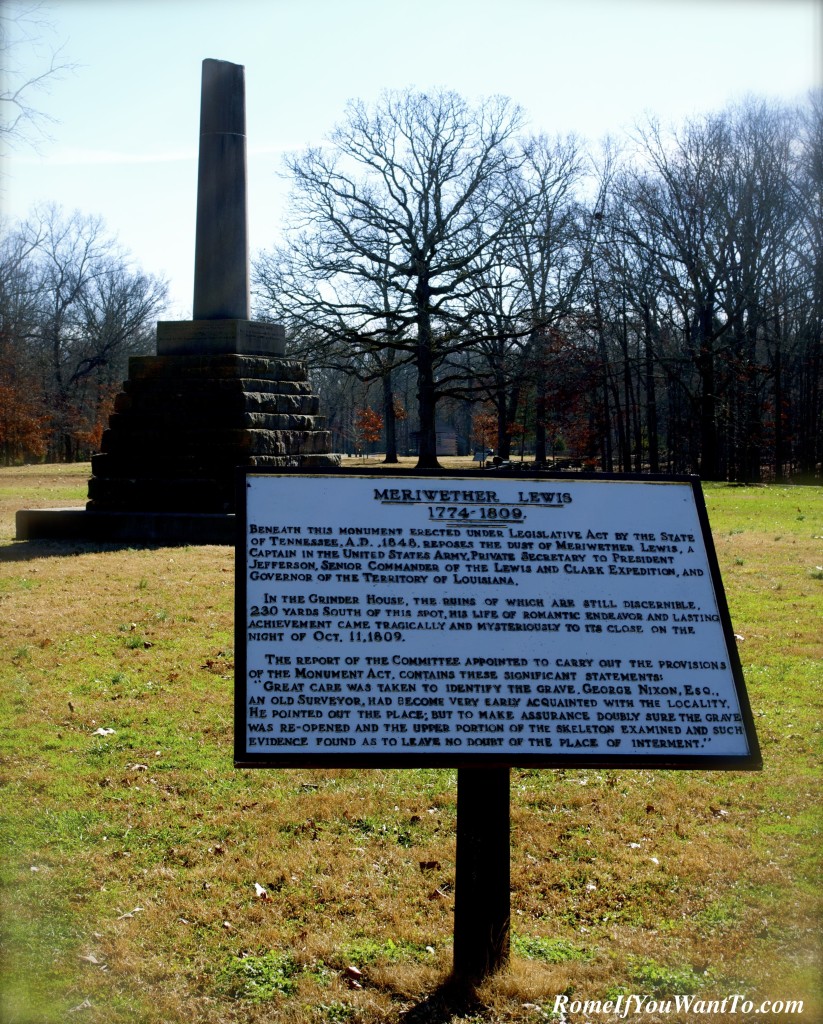

Some foundations of Grinder’s Stand are still linger, and on them, a replica has been built. It is a bit off of the road, surrounded by trees, which in December were bare, exposing the cabin to blue skies and sunlight that would be obscured in leafier months. It would have felt lonely, desolate even. With no one talk to the night he killed himself and with hundreds of miles to go before Washington, Lewis must have felt overwhelmed with solitude and helplessness. When you visit now, there is not much to see. A cabin, trees, a hiking trail around back, his grave (and the minuscule graves of other “pioneers,” unknowns, and even infants), and memorial monument a few hundred feet away, are about it. No museum, no portraits, no visitor’s center. I like this approach, because the place is remains time-capsuled.

I was happy to be visiting this sad place alongside my father, who knows the answer to every question about American history that one might ponder, and my aunt and uncle, with whom I have traveled much in Europe, and my dear cousin Alex, whom I have loved since he was born. I cannot imagine growing up in a household that doesn’t talk emphasize a love for history. One day in high school, I asked my father, “Where were Lewis and Clark from – Missouri?” “Don’t let your grandmother hear you say that,” he responded. “Those two were called the Great Virginians!”

After we left the Trace, we drove to historic Franklin, Tennessee for lunch at McCreary’s Irish Pub (very good food, really nice service). We ate shepherd’s pie and burgers, laughing, rolling our eyes at bad jokes, and grateful for each other.

It was a beautiful day. I tried to imagine a cold, dark October night in the woods, without the historical marker or nearby parking lot, and nobody to talk to.

No one and nothing at the landmark seemed to want to refer to Lewis’s death as a “suicide,” though most serious scholarship agrees that it was.

For one’s life to be called in death one of “romantic endeavor and lasting achievement” should be the goal of all men.

Monument to and tomb of Meriweather Lewis.

The nearby Pioneers’ Cemetery, containing the remains of over 100 early settlers of the area. Many unknown to us now, but once loved by someone.

An infant’s grave in the Pioneers’ Cemetery along the Natchez Trace.

********

If you like silliness and distractions from work, or miss my Random English posts, consider liking my Facebook page for daily funnies! And why not get this blog in your email? Use the handy link below.

Lovely post. Nature, history and family. What more is there to life?

Thank you, Pete!! I agree completely.